.Net DI Container Speed Test

You probably don’t care why I’ve done this, but if you don’t even care about most of the details of this test, let me lay it on you short and sweet: Autofac, Castle.Windsor, and StructureMap put out some excellent, consistent numbers; Spring.Net is middle of the road; Ninject is consistently the slowest of the pack by several orders of magnitude; and finally Unity showed such a weird behavior that made me question both the validity of my approach and the sanity of its developers (mostly kidding, ctavares is awesome). Note: there’s an update which examines some of the problems with Unity; you’ll probably want to read it.

I have elected to run against the latest versions of the six major containers of the .Net world: Autofac v2.4.5.724, Castle.Windsor v2.5.3, Ninject v2.2.0.0, Spring.Net v1.3.1, StructureMap v2.6.1, and Microsoft Unity v2.1.0.0 using the .Net 4.0 framework. I expect the results to be similar if you were to use 3.5; I could be wrong, but I don’t think any of them uses exclusive 4.0 features in areas that would make an impact on these results.

- methodology

- results

- retrieving singletons

- transient objects

- retrieving singletons - loaded containers

- transient objects - loaded containers

- my take

Methodology

My tests (source code available on github) concern themselves almost exclusively with the speed with which objects are retrieved from the containers. Memory footprint was not even a secondary concern and, to be honest, I don’t even know how to measure it with any kind of precision. The code contains a modest attempt at memory measurements - if you believe it to be correct, there’s a setting in app.config to print it out as you run the tests.

I believe there are two scenarios that are relevant to observing the performance of these containers: retrieving the same instance each Resolve<T>() call, i.e., singleton scope, and retrieving a new instance on each call a.k.a. transient scope. I don’t think either solution is what you would see in real life situations; most likely you’d encounter a mix of the two, with transient objects being injected with singletons and transients alike, but I couldn’t come up with a recipe that wouldn’t be easily dismissible on account of lacking balance in proportion of singleton to transient objects. At least taking extremes only leaves you to defend from one direction.

Resolving singletons tests the container’s raw retrieval speed and its registration internals. Creating new objects on each call tests the container’s build plan and the strategies it uses to match up objects.

All containers allow more advanced object lifestyles, e.g., single instance per thread or per HTTP request, but I don’t have enough confidence in my abilities (I’m also lazy) to come up with a clear strategy to produce measurements that are a) accurate, b) relevant, and c) somewhat equivalent across containers. However, I think the singleton and transient stories are somewhat indicative of other usage scenarios.

In both cases my program will load and configure all the containers then perform 10 runs of a loop requesting the same object a large number of times (10k and 100k) then average those 10 runs. I will refer to these two as the 10k run and respectively the 100k run. So that’s four combinations so far: singleton 10k, singleton 100k, transient 10k, transient 100k.

Finally, to add a fake real world flavor to the test, I will repeat the four test scenarios with the containers loaded with some significant number classes in order to simulate a container under some pressure and make 10k and, respectively, 100k requests of a number of objects randomly selected. I don’t think any container performs any kind of heuristic analysis of the requests with intent to provide a quicker resolution path for those objects requested more/most often, though I wish they did.

I am running this in a virtual machine that I will restart before each of the eight scenarios and then I will run the test program three times. I will post the numbers from both the first and third run, but will favor the third run for figures and charts.

Results

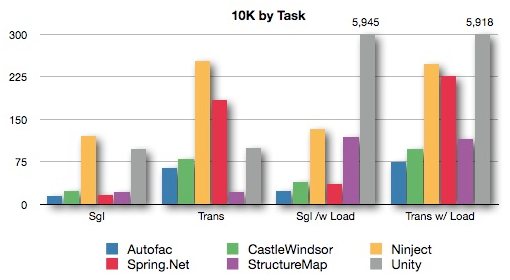

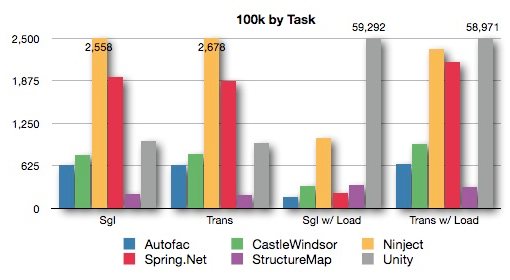

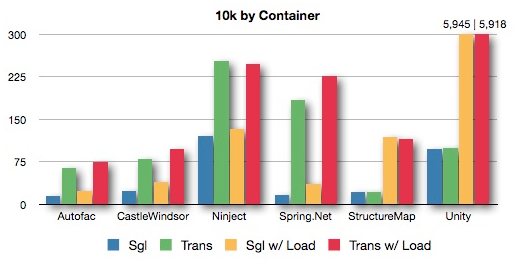

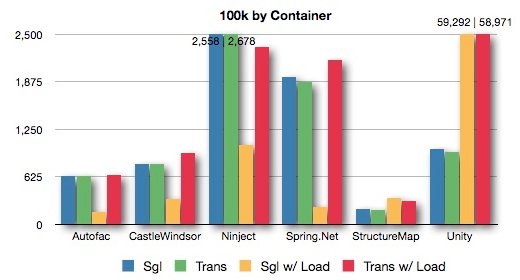

Individual results are boring, but are presented in the next sections for your perusal, so let us take a look at pretty charts presenting the overall situation.

I had to force a max value on the Y-axis (milliseconds) seeing how Unity completely blew the scales. As such, please pay attention to the scale on the left and occasionally to the number on top of the bars.

The chart of timings by task gives us a focused view and paints the relative behavior of containers within those groups:

Notice how Autofac, Windsor, and StructureMap behaved consistently well, Ninject behaved consistently badly (although that’s an exaggeration), whereas Spring.Net and Unity were highly irregular in their numbers.

Plotting the same numbers by container shows the areas of strength and weakness of each participant, but also how the containers behaved overall relative to each other:

We also get to see quirks, such as four out of six containers showing a dip in the 100k singleton loaded test relative to their other numbers.

All containers are roughly on parity syntactically and feature-wise - one can easily move from one to the next with little training, the only significant differentiator that I observed was elegance of configuration, but that’s hardly something to hang your project onto.

Let us look at individual numbers in ugly tables next. Feel free to jump to my take if this is not of interest to you.

Retrieving Singletons

I believe this is the most common case in construction of DI trees and it’s after all just an optimization of the transient scenario. It’s suitable for classes whose context remains unchanged through the execution of the program, be they complex or not. If you rely (solely? largely?) on the constructor flavor of dependency injection, chances are everything behaves as if it was in singleton mode anyway. However, if you use a Service Locator approach, whether exclusively or not, the difference between singleton and transient becomes something you have to pay more attention to.

Retrieving singletons is a case of configuring the containers to indicate that once an object is created, the same instance should be returned for each subsequent Resolve call.

// Castle.Windsor registration

k = new WindsorContainer();

k.Register(

Component.For<IDummy>().ImplementedBy<SimpleDummy>().LifeStyle.Singleton

);

// Retrieval

if (k.Kernel.HasComponent(typeof(IDummy)))

k.Resolve<IDummy>().Do(); // Do is void Do() {}The results of the runs:

: 10k - 1st 10k - 3rd 100k - 1st 100k - 3rd

------------------------------------------------------------

Autofac 15 14 688 635

Castle.Windsor 22 23 807 790

Ninject 123 121 2,616 2,558

Spring.Net 17 16 1,982 1,935

StructureMap 21 21 212 205

Unity 93 98 992 996

Median 22 22 900 893

Min 15 14 212 205

Max 123 121 2,616 2,558

The median across containers for Resolve()-ing the same object ten thousand times is around 20 milliseconds, with four out of six containers being close around that number. Of the two offenders, Ninject was 8.6 times slower than the fastest container, Autofac, and Unity close on its heels at 7x the speed. The 100k run only served to make the gap more obvious with Ninject clocking in a whooping 12.5x slower. Surprisingly, the second fastest container in the 10k run, Spring.Net was now the second slowest (9.4x slower).

Transient Objects

The transient scope is most common with classes that control access to limited resources: database connection, web service requests, etc., or whose context changes on every call. Or if you just want to be safer at the expense of a bit performance. My gut feeling is that in most cases these type of classes will have either creation or use costs that outweigh the container’s, but nevertheless I thought it makes for an interesting test case because it tells us how efficient each container’s build plan is. I don’t expect any of the containers to use the very slow Activator.CreateInstance, but there are various strategies that can be employed to create new objects and calculate their dependencies, all which can use different lifestyles.

As the test focuses on object creation I chose the route of an object with no dependencies, rather than the more complex but more realistic case of a class that gets injected with other dependencies, which themselves might be dynamically resolved at that point.

// Autofac configuration - defaults to transient lifetime

var builder = new ContainerBuilder();

builder.RegisterType<SimpleDummy>().As<IDummy>();

k = builder.Build();

// Retrieval

if (k.IsRegistered<IDummy>())

k.Resolve<IDummy>().Do();The results are, as expected, a good deal slower than the singleton scope scenario, except for StructureMap, which captured the crown once more:

: 10k - 1st 10k - 3rd 100k - 1st 100k - 3rd

------------------------------------------------------------

Autofac 64 64 710 634

Castle.Windsor 80 80 845 797

Ninject 255 253 2,575 2,678

Spring.Net 189 185 1,856 1,874

StructureMap 21 21 202 192

Unity 109 99 1,008 956

Median 95 90 927 877

Min 21 21 202 192

Max 255 253 2,575 2,678

I expected the 100k test to repeat the story of the singleton and to increase in the same proportion from the 10k figures, yet instead the numbers came close to those of the 100k singleton run, for all containers.

Ninject sticked to its guns and managed again to be 12x slower than the fastest container in the 10k race - StructureMap, and almost 14x slower in the 100k run. Worthy mention of suckage: Spring.Net, which managed slowness factors of 8.8 and 9.8 relative to StructureMap.

Retrieving Singletons - Loaded Containers

Based on what I’ve seen of their respective source code, each container takes different approaches to storing class registrations and as such when a resolution is performed, each container will use a different strategy to either retrieve an existing instance or create a new one (Unity calls them build plans, which I like a lot). I believe this test will attempt to show how well each container’s approach scales when the container has a good deal of objects registered and created.

I didn’t know what was supposed to be a realistic number of classes to saddle a container with, so I’ve picked pretty numbers. I’ve loaded each container with 666 classes registered for 222 interfaces (three name discriminators for each interface). I made then 10k and respectively 100k random requests, pairs of interface/discriminator, to resolve those registrations.

// StructureMap - registering named objects

ObjectFactory.Initialize(x => {

x.For<IDummy0>().Singleton().Use<SimpleDummy0>().Named("0");

x.For<IDummy0>().Singleton().Use<SimpleDummy1>().Named("1");

x.For<IDummy0>().Singleton().Use<SimpleDummy2>().Named("2");

x.For<IDummy1>().Singleton().Use<SimpleDummy3>().Named("0");

...

x.For<IDummy221>().Singleton().Use<SimpleDummy664>().Named("1");

x.For<IDummy221>().Singleton().Use<SimpleDummy665>().Named("2");

});

// Retrieval of named objects - SM doesn't have an IsRegistered

IDummy d;

if ((d = (ObjectFactory.TryGetInstance(t, name) as IDummy)) != null)

d.Do();On one hand I expected the figures to be a bit slower, but not by much. The containers should have efficient ways to sift through the registrations to find the proper resolutions.

: 10k - 1st 10k - 3rd 100k - 1st 100k - 3rd

------------------------------------------------------------

Autofac 25 23 166 163

Castle.Windsor 35 39 342 328

Ninject 128 133 1,053 1,040

Spring.Net 59 36 223 229

StructureMap 114 118 289 348

Unity 6,012 5,945 62,278 59,292

Median 87 79 316 338

Min 25 23 166 163

Max 6,012 5,945 62,278 59,292

What the!? What just happened? Are those Unity numbers real? 258.5 and respectively a whooping 363.8 times slower than Autofac. By contrast, it makes the usual suspect, Ninject, look like Formula-1 car.

Unfortunately it is true. I was so stupefied by the result that I had to try two different approaches on three different machines. They all posted similar numbers.

Transient Objects - Loaded Containers

You can probably anticipate how quickly I moved on to the next test. Unity has put an okay fight in the transient test, recording numbers on par with the other two usually fast containers: Autofac and Windsor.

Alas, even as the test was in progress (and it took forever and three cookies), I could tell there was no redemption. And sure enough:

: 10k - 1st 10k - 3rd 100k - 1st 100k - 3rd

------------------------------------------------------------

Autofac 73 74 806 645

Castle.Windsor 99 98 1,164 941

Ninject 248 247 2,683 2,338

Spring.Net 230 226 2,346 2,157

StructureMap 118 116 324 312

Unity 6,077 5,918 60,142 58,971

Median 174 171 1,755 1,549

Min 73 74 324 312

Max 6,077 5,918 60,142 58,971

I’m not going to dwell on those numbers. I don’t know how to explain them. I’ll just quickly mention Ninject posted only 3.3x in the 10k, but jumped back to 7.5x in the 100k. Spring.Net was the second slowest in the 100k, being 6.9 times slower than StructureMap.

My Take

From seeing these numbers, working with the containers (not just for the purpose of this test), and being somewhat aware of what tells them apart: my favorite is Autofac, which is small, incredibly powerful, and yet very elegant to use. In stark contrast to Spring.Net, I think I spent the least amount of time trying to figure out how to use Autofac - mostly everything seemed obvious. Even the more advanced features, some of which the other containers are either barely now getting them or still dreaming of them, are very straightforward and easy to pick up.

StructureMap is fast (see, I made it italic so it seems fast even as it stands still), but its documentation is a few versions behind, which makes it hard at times to figure out what’s the right approach to a given problem. It might be friendlier to introduce in legacy code, given it provides from the get go a Service Locator through its ObjectFactory static root, but given your level of comfort or abstraction needs you might choose to roll your own Service Locator. At any rate, thanks to the Common Service Locator project, you can abstract your DI container quite well. You might find StructureMap suitable if you need a very fast container when loaded with a lot of classes, but if that was a very important criteria I would definitely devise more suitable tests before jumping in.

Castle.Windsor is pretty much the veteran, yet it managed to stay nimble. It has one of the smartest guys in the industry behind it. It also has a few quirks here and there, and it’s not the most elegant to work with (name registration and retrieval in particular). I honestly cannot conjure a good reason to pick Windsor over Autofac, unless you are using the rest of the Castle framework.

At the opposite side of the spectrum: Spring.Net. A very powerful framework, especially if you travelled here from the land of Java, its DI/IoC container is just horrible to work with. I’ve always left it till the very last and punished myself for eating too many brownies by forcing me to complete the wrapper classes for the tests. I am aware of the CodeConfig project and its attempt to bring some sanity and an alternative to the hideous XML configuration files that Spring.Net otherwise employs (don’t even try to configure generics). It not only has spotty and slow performance, it’s actually quite unpleasant to work with.

Microsoft’s Unity is not a bad DI container; it used to be meh… at version 1.2, but starting with 2.0 - which took a very long time to come to light - it’s quite nice to work with. That is until you see these numbers and that’s seriously off-putting, no matter how many injection and extension features it offers. If you think about picking it up because it integrates well with ASP.Net MVC/Prism/EF/etc, well, so does Autofac.

Finally, Ninject - cool name, awesome website, bad performance. I would use it if the alternative was Spring.Net - but frankly can’t see why anyone would voluntarily choose it. Except if you want to be different, which sounds to me like a perfectly good reason.

Alright, we’re done. The source code is on github and once you read it you’ll probably want to contact me and laugh at something stupid I did in there. Or call me names. Or maybe just to talk about those hard to believe Unity numbers.