.Net DI Container Speed Redux

If you have an attention span as short as mine, feel free to skip to the TL;DR.

Following my previous .Net DI container speed test, a few people (thanks @slaneyrw, @roryprimrose, @JamesChaldecott) pointed out that the abysmal performance of Unity in both singleton loaded and transient loaded scenarios was largely due to checking for object registration before requesting. For example @roryprimrose detailed that :

@philipmatix The perf problem in Unity is actually in the IsRegistered call (35,347ms), not the Resolve (580ms).

A discussion on CodePlex with Chris Tavares and Grigori Melnik further denoted that, from Unity’s perspective, the use of

.IsRegistered is intended for debugging your apps only

With that in mind, I’ve decided to add tests that show the performance of containers when no registration checks were performed. Following the numbers and charts I’ll also provide my thoughts on why I believe both cases have merit.

Spoiler alert: Unity redeems itself, and although not quite the speediest container, it put out some pretty damn good numbers.

The rest of this post is broken down as following:

- performance without registration checks - in which we look at the numbers the containers yielded out when no registration checks were performed;

- the registration check debate - in which we talk about whether

IsRegisteredshould be performed at all; - alternatives to registration checks - we run a few scenarios that deal with optional dependencies - eschewing registration checks, and see the performance of those alternatives;

- conclusion - where I stop thinking.

Performance without Registration Checks

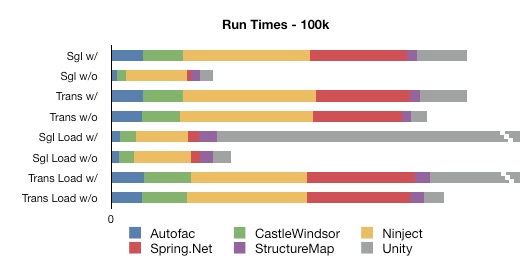

The following table displays the improvements that took place once the registration check was removed. I expected more impressive gains; I guess all containers but Unity have really efficient registration checks and as a result have only posted gains that hovered mostly between 1.1x to 1.3x, with a few weird numbers in between.

Sgl Trans Sgl - L Trans - L

10k 100k 10k 100k 10k 100k 10k 100k

Autofac 1.3 5.7 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.1 1.0 1.1

CastleWindsor 1.1 4.2 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.1 1.0 1.0

Ninject 1.0 2.1 1.0 1.0 1.1 0.9 1.0 1.0

Spring.Net 1.3 22.0 1.0 1.0 1.2 1.3 1.0 1.0

StructureMap 1.0 1.2 1.2 1.1 1.1 1.3 1.0 1.1

Unity 3.3 3.7 2.7 2.9 78.2 169.9 68.0 148.2

Of course, the big news here is that Unity, unencumbered by registration checks, posted speeds that were from 68 to 169 times faster.

To make it clear, the change in code was:

// Old and busted

if (container.IsRegistered<IDummy>())

return container.Resolve<IDummy>();

// New hotness

return container.Resolve<IDummy>();Another way to look at these numbers is to compare the contribution of each container to the total time it took each scenario to run. Of course, Unity’s trimmed out since it caused the chart to go nuts (to give you an idea this portion you see here is approximately 7 inches - Numbers’ measurements - out of 50 inches that was the size of the entire chart).

If it wasn’t obvious, “w/” indicates with registration checks and “w/o” means without registration checks.

An interesting detour for me was to try and get at least a superficial understanding of why Unity’s IsRegistered performed so poorly. As an extension method it doesn’t do much - it simply iterates over the unityContainer.Registrations picking up the one whose type matches the requested type. This is where things differ between Unity and almost all other containers: whereas those containers build their registries at the point where you register the types, Unity builds its list on each call to Registrations.

Indeed, each call to Registrations builds an IDictionary<Type, List<string>>, which is then filled in with types and names retrieved from the NamedTypesRegistry, here represented by registeredNames:

private void FillTypeRegistrationDictionary(IDictionary<Type, List<string>> typeRegistrations)

{

if(parent != null)

{

parent.FillTypeRegistrationDictionary(typeRegistrations);

}

foreach(Type t in registeredNames.RegisteredTypes)

{

if(!typeRegistrations.ContainsKey(t))

{

typeRegistrations[t] = new List<string>();

}

typeRegistrations[t] =

(typeRegistrations[t].Concat(registeredNames.GetKeys(t))).Distinct().ToList();

}

}Finally, on return, this dictionary is then transformed by a LINQ query into an IEnumerable<ContainerRegistration>.

It’s obvious that having this code executed 100,000 times, more so when loaded with a significant number of classes, will not win any performance awards.

If you are wondering, like I did, this was a conscious design decision, as indicated by Chris Tavares, who said:

Yeah, IsRegistered is not optimized at all - in fact, it’s almost deliberately suboptimal […]

(I left out a very important second part of his response, which I’d like to use in the registration check debate section).

Fair enough, it’s a decision I respect, and my intent is not to provide criticism, but a mere heads-up to fellow developers, given a great deal of people cheered the introduction of IsRegistered in Unity 2.0. Since I am quite fond of Unity, I’d very much like to see it brought on to perform on parity with the other containers, in all aspects.

The Registration Check Debate

In the same reply that I’ve extracted the quote above, Mr. Tavares asked a very good question: Why do you call IsRegistered at all?

, and expressed an opinion I share: if you’re using it a lot you’re most likely doing DI wrong

.

In broader terms, all these containers are truly IoC containers. IoC is an approach to handling object dependencies, a meta-pattern if you will, whereas Dependency Injection - which itself comes in about three flavors - is an implementation pattern. The other common IoC pattern is Service Locator.

I believe that even if Martin Fowler didn’t coin the two terms, he gave them the definition that people usually link to. You should read his article, but a very simplistic view would say that when you use DI you end up with all your dependencies injected in your classes, ready for use, whereas with SL you use a dedicated class to construct your dependencies right in the places in code where you need them. There are various use cases for either, but the general feeling, at least my feeling, is that DI presents a cleaner approach.

For all its cleanliness, Dependency Injection does require that you start without prior restraints. Not quite the case when dealing with a good mess of code where the High Cohesion, Low Coupling principle wasn’t even known to the developers, let alone employed in an effective way.

It is from this direction I came and, as Michael Feathers points in his seminal book Working Effectively with Legacy Code, Service Locator is an effective tool to help break tightly coupled classes (think of SL, if you will, as the gateway drug to DI). I think in part due to this type of situation, and I’m sure due in part to developers avoiding the DI because it requires a good deal more discipline, the presence of a SL in code is perceived as a good indication of code smell.

I got similar comments from other people. @dot_NET_Junkie was stronger in his statement, calling it an anti-pattern. Although not in such intense terms, I do share his feeling, but sometimes it’s not entirely fair. Given my use-case, decoupling classes so that I can eventually get to pure-DI, it would be akin to calling a crutch an anti-pattern when all you’re trying to do is get a little mobility waiting for your broken leg to mend.

At the end of the day, all that these containers provide is dependency resolution, how you employ them, whether pure DI or most likely a combination of DI and SL, it’s up to you. What didn’t escape me is the irony of the Service Locator being present even in the purest of DI cases: after all, how do you get that very first object, the root of your entire running hierarchy, out of the DI container? You ask for it, you get it, and there’s a name for that: service location. Glad we’ve established that; now we are just haggling about the price..

Alternatives to Registration Checks

There’s another interesting use case for a service locator, at least one in which it is considerably easier to employ it versus dependency injection: optional plugin points. What all these containers we looked at have in common is that when requesting an object that the containers cannot construct they will throw an exception: Unity throws a ResolutionFailedException, Ninject throws an ActivationException, etc. Given exceptions tend to be somewhat expensive in .Net, never mind the silliness of considering the absence of an optional component an exceptional case, it sounds reasonable that we’d check whether a component is registered before requesting it from the container.

But don’t trust me when I say exceptions are expensive - let’s look at some numbers. In the following benchmark I am trying to retrieve an object that is not registered and guard against it missing, first using IsRegistered and then by handling the exception thrown by the container.

public IDummy Run_IR(Type t, string name) {

if (k.IsRegistered(t, name))

return ((IDummy) k.Resolve(t, name));

return null;

}

public IDummy Run_Ex(Type t, string name) {

try {

return (IDummy) k.Resolve(t, name);

} catch (ResolutionFailedException) {

return null;

}

}The testing methodology differs from the previous cases, too. Instead of loading the containers with 222 interfaces (666 classes) from the start, I will load them progressively, starting with 1 registered interface (3 named classes) and going up increments of 20. Furthemore, as I do this because of my curiosity around Unity, I will only test it against Autofac (no other reason than it was the first one alphabetically). If you’re interested in the source code, you’ll find it in the ex_vs_isreg branch on github; the only relevant classes are VariableLoadAutofacRunner and VariableLoadUnityRunner.

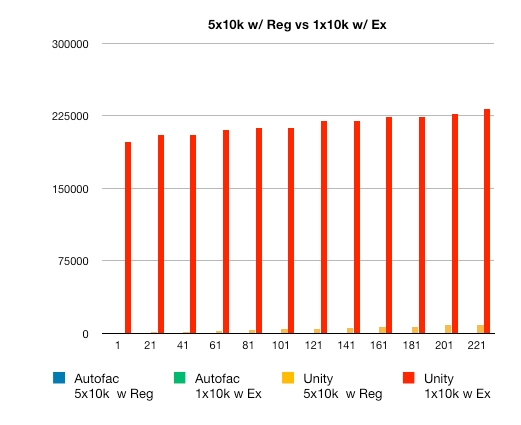

What I’ve learned? ResolutionFailedException is CRAZY expensive in Unity. Took me about two days to tweak the tests because I thought I coded an infinite loop. Here’s a useless chart:

Look at the values behind the chart, and yes, you’re reading it right - it took 43 minutes to run a single loop of 10k queries:

# Regs Autofac Unity

5x10k 1x10k 5x10k 1x10k

IsReg Ex IsReg Ex

1 4 508 70 198,241

21 2 378 803 205,340

41 2 376 1,571 205,370

61 2 375 2,296 210,353

81 2 378 3,061 212,034

101 2 378 3,876 212,431

121 2 372 4,712 219,162

141 2 373 5,277 219,637

161 2 565 6,397 223,136

181 2 375 6,774 223,365

201 2 375 8,012 226,826

221 2 374 8,720 232,349

Run time 26 4827 51,569 2,588,244

You can see that although exceptions in Autofac are about 150x more expensive than IsRegistered they don’t even hold a candle to Unity’s.

So exceptions are out, what else? Unity provides a built-in way to handle optional dependencies by the way of an OptionalDependencyAttribute that you decorate your injection points with. If Unity can find a dependency it will inject it, otherwise it will pass in null. The attribute is not the only way, as Chris Tavares wrote:

Optional dependencies can be configured the same way as any other dependency - through attributes, the API, or the config file. As such, you don’t have to put attributes in your code anywhere. Just resolve an object with the optional dependencies, and that object will get them injected (or not) if the container has a registration for it.

I have no reason to doubt him, but I was hard pressed to find either examples or documentation on how to handle them without the attribute. I’m sure that if you ask, either him or Grigori Melnik will happily provide such examples.

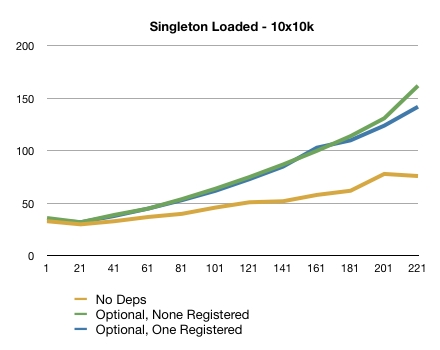

How does the OptionalDependency attribute handle? Quite well.

In the table below, the first column contains the progressive number of interfaces registered (x3 for objects), the second is the 10x10k run time for straight Resolve<IDummy>, i.e. where the classes had no dependencies, the third column contains the numbers for the dummies having an external optional dependency but with none registered to satisfy it, whereas in the third column there is a dependency to satisfy the constructors of the dummies.

# Reg Straight Optional, Optional,

None Reg One Reg

1 33 36 34

21 30 32 32

41 33 39 38

61 37 45 45

81 40 54 53

101 46 64 62

121 51 75 73

141 52 87 85

161 58 100 103

181 62 114 110

201 78 131 124

221 76 162 142

Very respectable numbers provided you are either ok with peppering your code with [OptionalDependency] (ugh), or use a config file (ugh), or you figure out how you can configure it through the Unity API (yay!).

There’s one more way - of course I left the best for last: the most elegant approach to handling optional components is to employ the Null Object pattern, in other words to provide a default, no-op implementation for all optional components. That way, you can use the container with no registration checks and get the excellent performance all containers provide, and when you have a specific implementation you simply override the existing registration in the container. As a supplemental benefit, the Null Object pattern saves you one of those ugly but required null checks.

Conclusion

The best use case for any of the six containers we looked at, now and a few weeks ago, Autofac, Castle.Windsor, Ninject, Spring.Net, StructureMap, and Microsoft Unity, and probably the best use case for Dependency Injection in general, is one where all your dependencies are satisfied. If you find yourself in this fortunate position, 4 out of the 6 containers produce results so close it’s not worth giving it a second thought - go with what you have or know. Even in the Ninject case, if you’re familiar with it, stick with it. Best you use any container than go without. If you’re forced to use Spring.Net, I’m sorry; I hope you reap the benefits of the rest of the framework.

If you find yourself employing a Service Locator pattern and Unity, examine whether you have a great deal of optional dependencies or, for that matter, any reason to perform IsRegistered checks. Best you don’t, whether you use Unity, or any other container. If you do need to deal with optional dependencies, go over the alternatives to registration checks - your best bet is the Null Object pattern, it’s a technique that works with all containers. It’s an awesome pattern in general, and one that applies greatly to almost all situations, not just DI, and yet, sadly, I don’t see employed enough.

The source code for my tests is on github. I have now created several branches for the various experiments we have performed: the original, using IsRegistered is in the with_isregistered branch; the direct Resolve without IsRegistered is in the without_isregistered branch; the attempts to measure the impact of exceptions in case of failed resolutions - for Autofac and Unity only - is in the ex_vs_isreg branch; finally, the examination of Unity’s performance with the OptionalDependencyAttribute is in the ex_vs_isreg_vs_opt branch (badly named because it doesn’t try to measure the performance of exception handling).